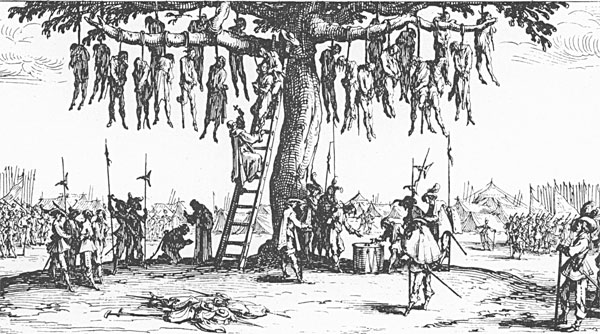

Artwork: Jacques Callot, "La pendaison" (detail), from Les Grandes Misères et Malheurs de la Guerre (1633). From Wikimedia.

Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form

Hillary L. Chute

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, $35 (cloth)

If violence is intrinsic to human culture, then the history of human violence is also the history of art. Greek vases from the fifth century BCE illustrate scenes from the Trojan War: blood spewing from the wounded Hector’s chest, a grief-stricken Achilles. Roman texts show images of war machines. The first purely informational literary work was a richly illustrated military how-to guide, Roberto Valturio’s 1472 De Re Militari (The Art of War).

In 1633 the innovative printmaker Jacques Callot published Les Grandes Misères et Malheurs de la Guerre (The Miseries of War), eighteen sequential prints depicting the horrors of what became known as the Thirty Years War: soldiers ransacking a farmhouse, raping its inhabitants as well as burning them alive; two dozen corpses hanging from a vast tree while onlookers chat casually a few yards away; public tortures and executions by burning at the stake.

Francisco de Goya’s Disasters of War print series (published posthumously in 1863) remains one of the most compelling statements against war. Created in response to the 1808 Dos de Mayo uprising in Madrid and the long conflict it spawned between Spain and Napoleonic France, Goya’s terse written comments suggest that he was a witness to some of the scenes: “I saw it.” “One cannot look at this.” “Why?” accompanies a picture of a man being bound and strangled by soldiers. “Barbarians!” editorializes a trussed man being shot point-blank. One of the most horrific images—the remains of mutilated, disarticulated corpses arranged on a tree—earns the sardonic, “A heroic feat! With dead men!” Goya makes viewers complicit in these horrors, unable to look away, despite his injunction.

Pictorial journalism became an increasingly popular form during the nineteenth century, when newspapers and magazines like Harper’s Weekly published the work of battlefield artists who produced on-site drawings of the Civil War. By the twentieth century, photojournalism was commonplace but still had not supplanted documentary illustration. The English artist Bruce Bairnsfather sketched his fellow soldiers in the trenches during World War I. According to the artist, his weekly Fragments from France cartoons in the Bystander showed those at home the “macabre and pathetic predicament of mutilated landscapes, primitive trench life, ceaseless wearing drudgery.”

The first cartoon documentary to be shown in theaters was also the first animation about a wartime catastrophe. Winsor McCay’s twelve-minute The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918) relied on eyewitness accounts to create the thousands of hand-drawn cells. McCay’s rendition of “the crime that shocked Humanity” resembled a contemporary newsreel, which in some sense it prefigured. Viewing the film remains a disturbing experience. Black smoke spews from the doomed ship as drowned corpses float in its wake. Hundreds of passengers leap to their deaths in scenes evocative of 9/11. The final, haunting image shows a mother sinking below the surface, helplessly trying to hold her infant above the water that swallows them.

One might think that a genre typically known to depict fantasy might be viewed skeptically as history. Indeed, Bruno Latour has argued that “the more the human hand can be seen as having worked on an image, the weaker is the image’s claim to offer truth.” Yet Hilary Chute argues in her new book, Disaster Drawn, that documentary comics are capable of unflinchingly representing events that verge on the unrepresentable—at times doing so better than media more conventionally associated with documentation, such as photography and film. This is because of what Chute calls their “plenitude,” the way they combine and juxtapose points of view, perspective, characters, chronology, and styles (in both words and images), allowing the viewer to become truly immersed.

Chute’s 2010 study Graphic Women explored autobiographical and sociopolitical narratives by comic book artists such as Marjane Satrapi, creator of Persepolis (2000). Her new book focuses on Art Spiegelman, Keiji Nakazawa, and Joe Sacco, whose best-known, groundbreaking works make readers experience atrocity at ground level: as Spiegelman says of Maus and Auschwitz, “It was a way of forcing myself and others to look at it.” In Disaster Drawn, Chute offers an elegant aesthetic and theoretical argument for how “made-up pictures” allow us to enter into traumatic historical events, “inviting one to look while signaling the difficulty of looking,” making them not only an accurate form of witness, but an ethical one. Chute thus underscores her main tenet: that the form of comics is inextricably tied to a moral response to trauma. This is not advocacy, as Chute writes of Sacco’s work, but the experience of history as “a kind of haunting by the other that does not end.” “Events are continuous,” Sacco writes in Footnotes in Gaza. “But the past and present cannot be so easily disentangled. They are part of a remorseless continuum, a historical blur,” not a liminal state of transition, but an immurement in the past that one is not condemned to repeat, but to confront.

• • •

Among the most significant documentary comics is Keiji Nakazawa’s 1972 Ore wa Mita (I Saw It: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima: A Survivor’s True Story). As a six-year-old, Nakazawa witnessed the atomic bombing of Hiroshima: he was shielded and saved from the blast when a concrete wall collapsed on him. His artist father and two of Nakazawa’s siblings were among the seventy thousand killed outright, as his pregnant mother watched. Traumatized, she gave birth that day to an infant who died four months later of malnutrition. Eventually she and her son found refuge with relatives outside the ruined city.

Like his father, the impoverished young Nakazawa was an artist. He drew on the backs of discarded movie posters, sewing the pages into books, and at an early age worked as a sign painter. Enthralled since childhood by the work of Osamu Tezuka, the legendary manga artist and activist best known to Americans as the creator of Astro Boy (which debuted in Japan only six years after the bomb), Nakazawa moved in 1961 to Tokyo to become a cartoonist. He did not disclose his experience of the bombing: after the war, the American occupiers and Japanese government censored mass media in Japan, outlawing mention of the devastation wrought by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the lingering effects of radiation poisoning. Within the resulting culture of silence and denial, survivors were known as hibakusha, “explosion-affected people,” stigmatized not unlike American AIDS sufferers during the height of the epidemic in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Nakazawa found work as a manga artist, and by the early 1960s was publishing generic manga—spy stories, science fiction, samurai adventures—in Boys’ Pictorial magazine. His mother’s 1966 death from radiation sickness shattered him. When he went to retrieve her remains from the crematorium, Nakazawa says: “There were no bones lef in my mother’s ashes, as there normally are after a cremation. Radioactive cesium from the bomb had eaten away at her bones to the point that they disintegrated. The bomb had even deprived me of my mother’s bones.”

In the aftermath of her death, Nakazawa wrote “Pelted by Black Rain,” his first fictional work about Hiroshima and the first Japanese comic about the bomb. It made the rounds of traditional publishers before finally appearing in 1968 in Manga Punch, a men’s magazine, where it was followed by four other atomic bomb–themed manga. In 1970 Nakazawa’s “Suddenly One Day” appeared in Boys’ Jump magazine, considered, like Manga Punch, to be a lowbrow rag. An unprecedented eighty pages long, “Suddenly, One Day” was the fictional account of a second-generation hibakusha whose child dies of leukemia, a result of his parent’s exposure to the bomb. It was many readers’ first encounter with both the facts of the bombings, and the lingering effects of radiation poisoning. The story triggered a huge public response (Nakazawa’s editor wept upon reading the story’s first pencil draft).

After the success of “Black Rain” and “Suddenly, One Day,” Nakazawa’s editor at Boys’ Jump encouraged him to create I Saw It, published as a stand-alone issue in 1972. Its grotesque images of shambling hibakusha and smoldering, melting corpses inevitably call to mind illustrations from horror comics like Tales from the Crypt and George Romero’s 1968 film Night of the Living Dead. Other scenes evoke the destruction wrought by Godzilla’s “atomic breath.” But Nakazawa transforms these horror tropes into an extraordinary act of witness: “he responds to the most high-tech of high technology, the atomic bomb . . . with the deliberately low-tech, primary practice of hand drawing.” Chute astutely notes that in I Saw It, Nakazawa recognized science fiction “as a genre of reality” that irradiated our world more than seventy years ago.

• • •

The first version of what became Art Spiegelman’s masterwork, Maus, appeared as a three-page black-and-white comic, “Maus,” in Justin Green’s anthology Funny Animals (1972). The story was later expanded, serialized in Raw, and finally published in two volumes, an edition that received the 1992 Pulitzer Prize, the first ever awarded to a comic book.

A fan of Harvey Kurtzman’s MAD Magazine, the wellspring of American underground comics, Spiegelman began drawing as a boy. “I was oddly imprinted very early like a baby duck with Mad,” he said during a 2011 conversation with Joe Sacco at the Pacific College of the Northwest. “It was like tree, rock, Mad. Once I realized that comics were made by people, I wanted to be one of them.” At eighteen he started doing freelance work for Topps, where he designed trading cards, most memorably the Wacky Packages series of stickers that sent up name brands, MAD-style—Neveready Batteries, Crust Toothpaste, Ratz Crackers, Jail-O—a huge playground hit for those of us who grew up in the late 1960s (and now highly collectible, if any readers still have theirs). After moving to San Francisco in 1971, he became part of the city’s flourishing underground comics scene and, like Nakazawa, published cartoons in second- or third-tier men’s magazines like Cavalier.

Spiegelman’s Polish immigrant parents, Anja and Vladek, were Holocaust survivors. Like the hibakusha, they did not speak openly of their experiences. The young Spiegelma first learned about the Holocaust from his mother’s “forbidden bookshelf,” which consisted of pamphlets written by survivors, many illustrated with cartoons. The often-crude production values and sometimes comically drawn characters underscored the stark horror of camp chimneys churning smoke and emaciated figures trapped behind barbed wire fences. Most of these booklets were printed after the war. A few were drawn by prisoners in the camps, like Horst Rosenthal’s Mickey au Camp de Gurs (1942), which featured Mickey Mouse imprisoned in the same camp as Rosenthal, who later died in Auschwitz.

After returning to New York, Spiegelman began compiling the massive amount of documentary material—written, visual, and oral—that he used to research and write Maus, including interviews with his father, Vladek. Just as Nakazawa draws on the imagery of pulp horror, Spiegelman deploys comics tropes, such as talking animals, to chilling effect. Maus’s mouse narrator, Mickey (Art Spiegelman’s alter ego), inhabits a world of George Herriman–inspired Nazi cats and Jewish mice. This choice was inspired by Spiegelman’s research, through which he discovered that Nazi propaganda often represented Jews as rats: “Posters of killing the vermin and making them flee were part of the overarching metaphor.”

Spiegelman has said that his work “materializes history.” In Maus, as in I Saw It, the bodies of the dead are revived and revised, by hand, on the page. Like their human counterparts, many are then disembodied again, executed or consumed by camp crematoria. In Maus, as opposed to the earlier three-page, densely crosshatched “Maus,” the reader’s identification with those in the concentration camp is heightened by what Chute calls a “shaggier” drawing style: “the specified features of the animal characters are replaced by a more minimal notational style—a visual system in which the reader cannot ‘take comfort,’ as Spiegelman puts it, that ‘it ain’t you.’” There is no comfort in Maus; it “goes into the camps and stays there at length, re-creating a world meant to be studied and engaged at one’s own pace.”

Maus’s publication was a game changer for comics, the moment when the medium came of age as a documentary form worthy of scholarly study and serious critical attention. With regard to the latter, Spiegelman insisted on no less. In a 1991 letter to the editor of the New York Times, he took the newspaper to task for placing Maus on the fiction bestseller list.

. . . to the extent that ‘fiction’ indicates that a work isn’t factual, I feel a bit queasy. As an author I believe I might have lopped several years off the 13 I devoted to my two-volume project if I could only have taken a novelist’s license while searching for a novelistic structure. . . . I know that by delineating people with animal heads I’ve raised problems of taxonomy for you. Could you consider adding a special ‘nonfiction/mice’ category to your list?

The Times responded:

The publisher of Maus II, Pantheon Books, lists it as ‘history; memoir.’ The Library of Congress also places it in the nonfiction category: ‘1. Spiegelman, Vladek -- Comic books, strips, etc. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945) -- Poland -- Biography. . . . 3. Holocaust survivors -- United States -- Biography. . . .’ Accordingly, this week we have moved Maus II to the hard-cover nonfiction list, where it is No. 13.

• • •

Like Spiegelman, Joe Sacco is the son of immigrant parents, who survived German and Italian airstrikes on Malta during World War II. Born in Malta, Sacco lived in Australia until 1972, when at the age of ten he moved with his family to the United States. He received a bachelor’s in journalism, and although he cites the New Journalism of the 1960s and ’70s as a major influence, he grew disenchanted with a journalistic career after college. He moved to Malta, where he created the country’s first narrative comic, before returning to the United States. He founded an alternative comics journal and did satirical comics work before becoming engrossed in the ongoing Gulf War. This led to Palestine, which was published in nine installments beginning in 1993, received the American Book Award, and was collected as a standalone work in 2001. His later works, Safe Area Goražde: The War in Eastern Bosnia 1992–95 (2000), The Fixer: A Story from Sarajevo (2003), Footnotes in Gaza (2009), The Great War (2013), and Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt (2012, with Chris Hedges) all explore “how history becomes legible as history.”

An on-the-ground journalist, Sacco immerses himself in the lives of those who lived (and are living) through conflicts that have torn their countries and lives apart. His crowded pages, the result of Sacco’s “saturation reporting,” are dense with meticulously drawn, almost photorealistic details. Sacco calls his work “slow journalism.” One can get lost in the pages for hours.

Sacco never loses sight of individual bodies, dead or living. He writes: “You see extremes of humanity in places like Palestine and Bosnia. . . . Mostly what you see is innocent people being crushed beneath the wheels of history.” His work expands the limits of what can be documented. In “A Thousand Words,” a six-page installment of Palestine, Sacco recounts his unsuccessful attempt to photograph Israeli police brutalizing a peaceful protest of Palestinian women and children. He was not standing in the right place to get the shot. “There’s nothing here,” an editor tells him. A camera limits what an artist can capture in ways that drawing does not: Sacco eloquently explains how the comics artist’s ability to place himself anywhere within the frame can surpass even a camera, to capture Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “perfect moment.” “When you draw, you can always capture that moment,” he writes. “You can always have that exact, precise moment when someone’s got the club raised.”

Sacco’s close-up drawings put the reader in a crowd being attacked by Israeli soldiers as the club slams down. Palestine’s final, black frame underscores the brutality of everything we’ve read so far, but also might suggest a tabula rasa for beginning a new story. In the Middle East alone, myriad artists have joined Sacco in creating comics of witness, including Magdy El Shafee’s Metro: A Story of Cairo (2012); Wajdy Mustafa’s Levant Fever: True Stories from Syria’s Underground (2015); and Ari Folman and David Polonsky’s animated film Waltz with Bashir (2008). In a world in which sophisticated photo editing has taught the savvy viewer to approach purportedly documentary photos with due skepticism, pictorial journalism—trustworthy, ironically, for the undisguised nature of its contrivance—might in time achieve nearly equal footing with more conventional documentary forms.

• • •

In her introduction to Disaster Drawn, Chute recalls Roland Barthes’s visionary 1970 essay “The Third Meaning,” which analyzes still frames from Sergei Eisenstein’s 1944 film Ivan the Terrible. The essay was also one of the first to describe the ability of comics to “open up the field of meaning through its dual inscription and mobilization of time.”

Barthes notes the two most common ways a viewer responds to a film or series of related images. The first is largely informational: we register the characters, settings, costumes, time frame, and dialogue, and from these construct a narrative that interprets the series of images. The second meaning is symbolic. Whatever information we’ve already absorbed can be deepened, and our perceptions perhaps altered, by an image’s symbolic or metaphorical weight: a clenched fist; a bowed head; teeth bared in a grimace that might be a snarl or smile.

There is a third, subtler hermeneutic Barthes identifies, which he terms the “obtuse meaning.” This meaning derives from the profound pleasure found in a purely visual depiction. Think of the sublime moment in Chris Marker’s 1962 La Jetée—a film consisting solely of black-and-white still frames, except for when we see the motion of a woman’s eyes suddenly opening to gaze into our own. It is the moment that can only be experienced in film or another diegetic art, Barthes states, “namely the photo-novel and the comic-strip. I am convinced that these ‘arts,’ born in the lower depths of high culture . . . present a new signifier.”

In comics as with film, our recognition of the artist’s hand and eye elevates our experience from that of passive viewer to engaged witness, even as we acknowledge the unreality of what we see. As film critic Matt Levine wrote in a blog about Barthes’s essay:

In the fissures and cracks of the filmic image, when we realize that pictures on film are indeed unique in a limitless number of ways, the transfixing real-unreal rift by which cinema operates becomes quite clear. This is what the third meaning is about: realizing that these images are illusions, and becoming simultaneously enraptured by how immersive, striking, and real they are.

It is this real-unreal rift that Sacco explores so memorably in his work: “the past and the present cannot be so easily disentangled,” he says in Footnotes in Gaza. “They are part of a remorseless continuum, a historical blur.” And while photographs that claim historical accuracy can be faked, provoking outrage, we know (and trust) that the artist’s hand and eye have collaborated to create the images we linger over in the work of Sacco, Spiegelman, Nakazawa, and the emerging artists whom they have inspired. They render the unspeakable in a language we can all understand, conjuring voices and histories that might otherwise go unheard.

Originally published on BostonReview.net.